There is No Devil, There's Only God When He's Drunk

One of the great challenges of making sense of the world is our natural human tendency to reify our favourite ideas/theories: becoming so convinced by a concept that you begin to believe that it is an actual thing in the world and not just an idea in your head.

Reification

We reify Money, for example, believing that it is a real force in the world; rather than a symbol onto which we project our desire for ease, comfort, social status, and power. What makes money work is simply and only that we believe it does, and because we make it work, it works; and so we believe it is real.

Time is another example, and of all things, we reify time perhaps most intensely of all, because it allows us to get our hands on something that is frustratingly ephemeral and elusive. The ticking of a clock represents time, but is not time itself. The rising and setting of sun and moon, the passing of the seasons also mark time, but are not time. We don’t even definitively know if time actually passes, let alone whether it passes through us, or if we pass through it…

A different Kind of Thing

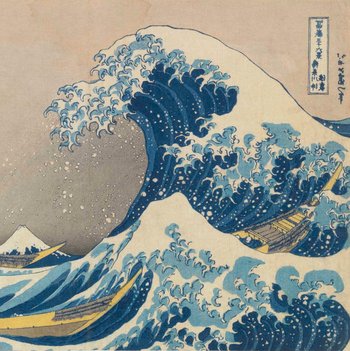

To bring this into the realm of psychology and psychotherapy, just about everything we talk about in these subjects are reifications. Sadness doesn’t exist as a physical entity, any more than happiness does, any more than anxiety, depression, or psychosis do. Thoughts also don’t exist as actual entities, any more than the waves on an ocean are an object. A wave is not an object in the water, it is the water, and the water is waving.

Similarly, a “think” is a wave in the ocean of our mental processing; a think is not an object in the ocean of your mind, it is your mind, and your mind is think-ing. (“Mind”, by the way, is also a reification, and one just as hotly debated as “time”.)

So, there is certainly a sense in which a thought (or an emotion, or a feeling) is a thing, but if the thought “I’m super confused right now” is a thing, then it a very different kind of thing than, say, a doorknob or shoe.

A Useful Ability

We refer to and think of emotions as if they were things because it is very difficult to succinctly articulate exactly what surprise feels like (or irritation, or ennui) and there are no words (in English, anyway) for most of the sensations comprised by, say, exasperation. So it’s helpful to have a shorthand and save yourself a bunch of extraneous explanation. Also, like time, emotions are frustratingly ephemeral and transitory. So we use our mental abilities to make real-seeming “things” out of intangible and transitory states of metabolic and cognitive arousal. This gives us something to hold onto when talking to others about what we are experiencing.

Like money, however, our reified emotional concept-things quickly become real-because-we-believe-they are, and therefore they also become a powerful conduit for our projected desires and aversions. Most of us feel a dreadful longing to “have” more happiness, but don’t understand why it’s impossible to “get” it. We long to “get rid of” sadness as you would strip a building of its asbestos heat insulation, but find that not only is there no asbestos, there is no building. Happiness and sadness simply don’t work that way. Nor do depression, anxiety, mania, intrusive thoughts, or frustratingly-resilient-attachment-feelings-towards-an-abusive-romantic-partner.

So, the main problem with how we talk about emotions is the same one we have with money. We talk about them as objects, because we believe they are objects, because we talk about them as objects. Thus we expect them to be objects and behave like objects, and we get very confused and upset when they don’t. In this way, we create our own unhappiness, by setting up the conditions for perpetually being disappointed.

Back-Asswards

This makes reification a real challenge (see how hard it is to avoid? Challenge is also a reification…) for all of us, and it takes a surprising amount of introspection and emotional effort to learn how to experience your emotions for what they are: transient states of feeling and thought; the body’s signals to itself about how it is doing at any given moment and what it needs to continue surviving.

In terms of psychology, the issue with reification is that it also works in reverse. Unlike a shoe, you can’t draw a unicorn and then claim that because you drew it, unicorns must therefore exist in real life. Most of modern psychiatry, however, is based on psychological unicorn-paintings, ie. pre-conceived categories of experience (aka. diagnoses and mental diseases) for which it then cherry-picks evidence to prove that the unicorn is real when it actually isn’t.

Anxiety is Not a Shoe

A picture of a shoe is not a shoe, but it refers to one. A description of anxiety symptoms is not only not Generalised Anxiety Disorder, but it doesn’t even refer to Generalised Anxiety Disorder, because GAD doesn’t exist. Not only does GAD not exist, if it did, it wouldn’t be a disorder, because there’s nothing wrong with being anxious about something that worries you. You might be worrying more than you need to about things that you don’t need to worry about, but that doesn’t mean you have a mental disease called GAD.

The problem with medical categorising/diagnosis is the same as every other kind of reification: We talk about “bipolar” as if it were real, and so we believe it is real, because we talk about it as if it were real, because we believe it is real. And because we expect it to be an object and behave like an object, we become very frustrated when we can’t just open up our heads and replace the broken spark-plug. (Pills and powerful drugs being the medical attempt at said spark-plug.)

These days, what often happens before people go to a psychiatrist is they look their weird/bad feeling up on the Internet (also a reification!), and then the Internet tells them that they have a thing called “Insecure Attachment” (or whatever). The more they read about it, the more they become convinced that they do in fact have this thing, “because, look, I have so many of the symptoms.”

In other words, on the basis of the authority of collective belief, I become convinced that some arbitrary and inaccurate category of “disordered” experience is not only a real object, but also that this foreign entity has somehow gotten into my brain!

This is then “confirmed” by a list of uncomfortable sensations and experiences that appear to be connected with the specific “disorder.” Unfortunately, for me, each one of these “specific symptoms” are also associated with a bunch of other so-called disorders. And suddenly I discover that no only am I insecurely attached, but I also “have” bi-polar, schizophrenia, ADHD, early-stage heart disease, and a terrifying and incurable form of brain cancer.

One-Self, Two-Self, Three-Self, Four

I like to rag on psychiatry a lot, so let’s take an example from closer to home. Psychology and psychotherapy also have an obsessive and probably unhealthy love-affair with reifications, and each subject is chock full of real-because-we-believe-they’re-real concepts: from Confirmation Bias, to Freud’s Id, Ego, and Supergo, to Identity, to the very idea of the Self itself. A particularly good (and relatively simple) example of this is the False-Self concept.

True/False

This is the idea that within everyone there is a “true” self and a “false” self. Where the true self comprises all of your honest thoughts, feelings, and desires, the false self consists of all of the things you do, think, and feel because you are socially obligated, or feel like you’re obligated to do, think, and feel them.

Doing and saying things that don’t align with your values and desires is profoundly uncomfortable, but many people do it for so long that they become used to it, and begin to believe that the “false” self is who they actually are. Then they’ll have some disruptive or revelatory experience (a car crash, a bad breakup, a mushroom trip, or an intense therapy session) and they’ll suddenly realise that they’ve been so taken over by the “false self” that they no longer even know who their “true self” is.

I actually quite like this idea, because it makes it much easier to talk about nebulous themes like identity, will/desire, compliance/conformity, and so on. But if you pay close attention to your own thinking and feeling, as you talk more and more about the False Self idea as an idea, you can feel yourself becoming ever more convinced that there really is a real other you in there that is “false”.

There Is No Devil, There’s Only God When He’s Drunk

But there’s always a but…

The False-Self concept is very useful one, but… there is no false self, any more than there is a true one. Any more than a wave is an object inside of an ocean.

The False Self and True Self are not separate entities within a person: The false self is me behaving incongruently, and the “true” self is also me, but behaving congruently. Notice, both of them are me.

Good Old Denial

Personally, I have to admit that part of the reason why the False-Self idea appeals to me is that the imaginary split between true and false selves allows me to shunt responsibility for being dishonest with myself and hurtful to others onto “someone” who is “in” me, but isn’t me.

If I’m being honest then, I have to admit that as useful as it is, I’m actually reifying the False-Self concept and using it in the service of two very sneaky defense mechanisms: denial and rationalisation.

It Seems So Real

The hard part is that once you become convinced that there is a true and false self within you, it really does feel like they really are there. This is partly because behaving incongruently is inherently alienating, ie. it creates an emotional tension which feels like you are being split down the middle.

As I said, conceptualising this experience is extremely useful, if only because it allows you to acknowledge for the first time that how you are now is different from how you want to be. The rationalisation and denial defenses play their positive parts too: they protect you from the guilt and shame of having deceived yourself for so many years and allow you to start making the changes you need to make without (too much) embarrassment. But eventually I have to admit to myself that by leaning on this concept, I’m still deceiving myself.

Through the Looking Glass

You can’t paint a picture of a unicorn and then insist that unicorns exist because you painted one.

This, ultimately, is the main problem with reification: it’s very convincing. We all have an innate desire to understand the world, and the concept-objects we create give us simple and satisfying answers that allow us to stop worrying and get on with the actually important part, surviving.

This is partly why people so often turn nasty when you challenge their fundamental beliefs, most of which are reified concepts (capitalism, the holy trinity, Che Geuvarra, blood purity): you are threatening to remove the foundations of their entire understanding of the world.

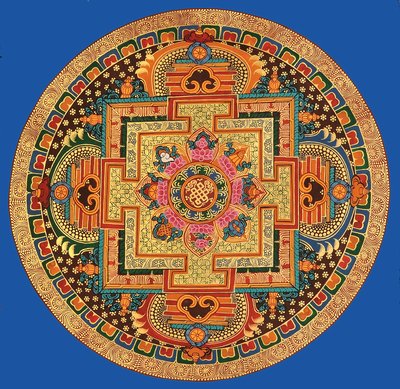

Yet, the whole goal of emotional, intellectual, and spiritual development (whether through psychotherapy, psychedelics, or spiritualism in whatever form) is to learn to see through the veil of real-but-imaginary beliefs to the actual reality hiding in behind.

Another Turn of the Wheel

I’m really not saying anything new here. The above criticisms of reification have a long history that extends back across thousands of years through most of the worlds religious and spiritual traditions. And critics of psychiatry have been saying all of this stuff since psychiatry was invented (and therefore psychotherapy, as a branch of OG psychiatry).

There are, for example, many good and convincing arguments for why we should abandon the DSM and ICD “mental disease” classification systems; because they do more harm than good. And there are already a number of very strong alternatives which do a much better job of actually helping people who are suffering emotionally.

But reification is such a powerful aspect of human thinking and feeling that even once you understand it and identify it within yourself, you still have to constantly remind yourself that your favourite concepts are just concepts and do not exist in the way you feel they do.

Ultimately, reification results from our desire to simplify the world enough for our little and limited human brains to comprehend at least some small part of the inconceivably vast and complex reality we inhabit. This is a very useful ability, but it is also one that can easily run away with us.

Creating, using, and reifying concepts doesn’t have to be problematic, as long as we remember that a concept is a thought, and a thought is a think, and a think is a wave on an ocean that never stops waving.