On Metaphor

There is nothing quite so satisfying as finding the perfect metaphor to describe a complex thought or experience. A good metaphor brings with it a kind of settling feeling, as if you’ve finally found a permanent, but unobtrusive space on the shelf for that old vase your grandmother gave you, that you don’t much like, but also don’t have the heart to throw away.

It’s finding the perfect parking spot right by the elevator in a totally packed parking lot. Or putting in the last piece on the edge of a large and complex jigsaw puzzle—you know you’ve a lot more work to do, but you feel real accomplishment at having made a good start.

Familiar and Easy to Understand

In therapy, the main value of metaphor is this feeling itself: it allows you to take abstract, and difficult-to-explain thoughts and emotions and turn them into tangible, familiar objects and processes. You give yourself something to grab onto, and you finally get to feel like you actually understand something about yourself.

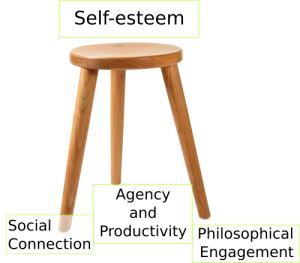

For example, self-esteem is a hopelessly ill-defined concept. Almost nobody knows what anybody else means when they use the term, because self-esteem isn’t a thing you can point to. It’s a non-physical idea that refers to a psychological orientation towards the world that allows you to feel confident while making both decisions and compromises, so that you get what you need while retaining your self-respect.

But if I say that self-esteem is the “seat” of a stool with three legs, you can immediately get a sense of what it comprises and how the parts relate and interact. And if we name the three “legs,” social connection, agency and productivity, and philosophical/spiritual/religious engagement, the picture becomes even clearer.

Of course, self-esteem doesn’t literally work like a stool with three legs does. Furthermore, you could argue that the stool should have 4 legs and a backrest, and maybe a bit of padding for you to sit comfortably on.

Which is exactly the idea: as you build the image, you refine your understanding of the system it represents. In other words, creating a metaphor helps clarify the aspects involved and how they relate.

Clarifying and Refining Our Understanding

This clarifying and refining function makes metaphor and analogy incredibly powerful tools in psychotherapy.

One of the hardest parts of managing and healing emotional and psychological suffering is how confusing and overwhelming it all is. Metaphorical thinking doesn’t “cure” our overwhelming emotions, but it does allow you to take break from them for a while. And, more importantly, you start to move towards understanding yourself, rather than running away from the frightening things within you.

Even the smallest understanding of how it all fits together is enough to give you the feeling that you’re starting to get a handle on things. You can understand it all.

And if you can understaind it, you can fix it.

Creating More Confusion?

The two main arguments against metaphorical thinking are:

- It leads to misleading over-simplifications.

- It allows us to invent facts and events that make for a pretty picture, but which don’t actually reflect reality.

Both of these can be an issue in therapy, because, indeed, the emotions we struggle with are often very complex. And secondly, a big psychological challenge for many people is establishing what is actually true, and what is imagination and/or projection. And so, it might seem that thinking and speaking metaphorically will only confuse things more.

Somewhere to Start

But, nobody who wants to learn math would ever start with calculus; the first book all of us read in school was definitely not War & Peace; and no pianist ever had their very first lesson on stage in front of 20,000 people.

In other words, learning a new skill requires you to start simple and move at a pace that works for you.

As with the metaphor of three-legged stool of self-esteem, it’s never going to be a perfect match, and there are lots of ways to change the diea, but working with a simple image helps you identify the core features of the thing you’re trying to understand. It’s somewhere to start.

Secondly, identifying all of the places where a metaphor doesn’t match reality is just as helpful as creating it in the first place. There are many ways in which learning to manage emotions is utterly unlike learning the piano, or being on stage in front of 20,000 people, for that matter.

Teasing these things apart helps you create a more nuanced understanding of your emotions and your experience, and therefore of yourself. Which is the major goal of psychotherapy in the first place.

Of-a-Piece with Yourself

First and foremost, therapy is about learning that you don’t have to be afraid of your emotions. Even though you can’t control them directly, you can influence your emotions, and you can decide whether or not to act on them. So although it sometimes feels like it, you are not locked in a stagecoach being dragged towards the edge of a cliff by a team of wild horses. Which is to say, you are not a mind trapped in a runaway body that you can’t control.

We are not buggy and driver, nor are we horse and rider. We are like the centaur or the sphinx, half animal, half rational; a complex system consisting of two seemingly incompatible aspects which somehow combine well enough for us to think, to feel, and to be active, intentional agents in the world.

But we are also not two separate creatures magically joined at the waist. Our thoughts explain our emotions, and our emotions respond to our thoughts. We can separate them metaphorically, but in reality they are of a piece and inseparable. Metaphors are incredibly helpful, but they’re also not the whole truth.

Engaging with the Process

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter what the final product looks like, the important thing is the process of creating it. Therapy is about engaging with your emotions and memories in a way that takes the fear out of the equation so that you can be honest with yourself and the people in your life.

And so, creating metaphors is a way of disarming the emotions, thoughts, and memories that scare us. It is a way of playing with our experience, and rearranging our feelings into patterns that feel right and true, and above all, that make sense. Even if nobody else understands, we do, and that’s the whole point of starting therapy in the first place.